When Kyle felt the whoosh of the 400-ton airplane lift from the tarmac into the hot Atlanta sky at 180 mph, he had an epiphany.

“I found my purpose. This is what I want to do with my life.”

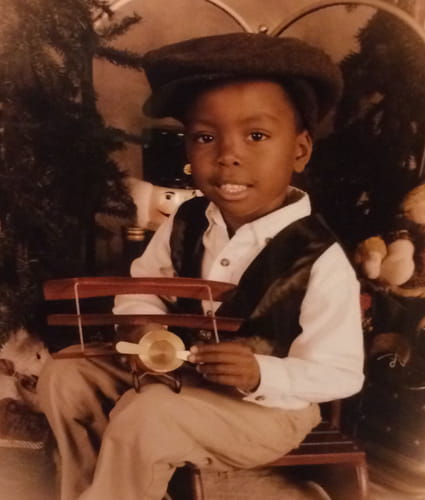

He was only 5 years old. Every Christmas after that, he asked for toy airplanes to replace the ones worn out from use. He wore pajamas patterned with passenger planes, slept in blankets emblazoned with fighter jets, toted a lunch box of Disney’s Dusty Crophopper.

At 13, his dad took him on a flight with an instructor. Kyle got to control the plane. He felt at home in the cockpit, in the clouds, with the birds.

“It amazed me. I had no doubt I was meant to be a pilot.”

At 16, he found out he could never be one.

An inherited blood disorder called sickle cell disease meant Kyle would be grounded for life. The altitude would trigger a painful reaction, making it unsafe to fly a plane. A school counselor told him he’d have to find something else to do with his career. What was his backup plan?

“I told her I didn’t have one,” he said. “She said I had no choice.”

At the time, that was true. Kyle would never have been able to peer down at the world from 35,000 feet doing his favorite thing in the world.

But now, new gene therapies have changed everything. A one-time infusion can correct the genetic mutation in patients with sickle cell disease, essentially curing it.

The caveat: the two FDA-approved gene therapies aren’t accessible to many patients because of their cost. Fortunately for Kyle, his treatment was free through a clinical trial.

“It completely changed my life,” he said. “And I want everyone out there with the disease to have the same access and same hope.”

The reality of sickle cell disease

Kyle couldn’t play tag at recess. Kyle couldn’t join the football team. Kyle couldn’t camp.

Kyle couldn’t.

Sometimes it felt like his tagline.

“It was hard to not make sickle cell my identity,” he said.

If Kyle exerted himself too much or got too hot or didn’t hydrate, shards of pain would ripple throughout his body. During his childhood, he ended up at the hospital every month for a week when the pain got so bad he couldn’t function.

Or when the pain got so bad he wanted to die.

“During one of my hospital stays, I told my dad I wanted to go be with the Lord,” he said.

With sickle cell disease, the body can’t make healthy red blood cells. The stiffened, sickle-shaped cells, which are supposed to be flexible and round, clump up in inflamed blood vessels, like grease in a pipe. This keeps oxygen from getting to the body’s tissues, causing a host of serious, chronic, and lifelong health issues.

Some kids will have a stroke. Some will need organ transplants. Others, like Kyle, will have extreme pain episodes. Most will die before they turn 50 — about 30 years earlier than the rest of the population.

“Some of the manifestations are very disabling, and some are catastrophic,” said Suhag Parikh, MD, clinical director of cell therapy for non-malignant diseases at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “Most patients have decreased life expectancy, but a subset lives much shorter lives and have lot more problems.”

What are small issues for most people become big issues for those with sickle cell. A simple cold can result in a blood transfusion, a high fever can cause uncontrolled pain, an infection can lead to death.

Kyle missed countless days of school. He suffered continual episodes of extreme pain. He never had energy. He always had doubt.

“It affects your confidence going out into the real world, because you're not as independent. You know you’re different,” he said.

For some kids, sickle cell disease improves after puberty. But Kyle’s doctor said his would likely never get better. If anything, it would get worse.

“We felt hopeless,” he said.

A new hope for sickle cell treatment

Meanwhile, across the globe, a Parisian boy was making headlines as the first person in history to be treated with a novel gene therapy for sickle cell disease.

Doctors had removed some of his stem cells, fixed the genetic code responsible for the malfunction, and returned it to his body. Soon he started producing round, healthy blood cells.

Kyle discovered the same therapy would be available in clinical trials in the U.S. the next year. And his home children’s hospital, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, could provide the therapy.

A new life

After graduating high school, on his 19th birthday, Kyle’s stem cells were collected and sent out for repair.

“I like to call it my rebirth day,” he said.

A few months of blood transfusions and a few days of chemotherapy got rid of his old cells to make way for the new.

And then the genetically altered cells went back in. They travelled to the bone marrow, settled in, and started churning out red cells with healthy hemoglobin that wouldn’t choke or sickle. Once his immunity levels looked good, he was released from the hospital and closely monitored.

“His outcome is excellent,” said Parikh, who monitored his recovery. “He always comes in, and I'm expecting him to say that he’s had pain. But no, absolutely no problems. It’s very gratifying to see that.”

He’ll never have another blood transfusion, another hospital stay for pain, another “couldn’t.”

Kyle is one of the fortunate ones. Very few people with sickle cell disease have received these therapies, in large part due to their complexity and cost.

They require extended hospital stays and highly specialized care from a team of providers. The list price for each of the FDA-approved infusions ranges from $2.2 million to $3.1 million.

These and other factors present access challenges for children who desperately need treatment. Some states have agreed to a new CMS model to help improve access for children with Medicaid. The Children’s Hospital Association hopes more will join.

Back in the blue skies of Georgia, Kyle is flying high.

“Since starting the medicine, I haven’t had a pain crisis,” he said. “It’s allowed me to go out and pursue my dreams.”

He earned a private pilot license, and he’s training to fly commercially. His excitement at 23 hasn’t waned since that first takeoff at 5 years old.

“It amazes me every time,” Kyle said. “When I’m up there, I never want to come down.”