With nearly three decades as a pediatric emergency medicine physician, Natalie Lane has seen traumatic injuries, unprecedented surges and a global pandemic, up close. No stranger to emergency is she. Still, she carries one weight that never seems to get lighter.

“One of the hardest things is when a parent comes to the children’s hospital thinking we should be able to take care of everything here—and I have to turn around and say there are no beds,” says Lane, M.D., FAAP, medical director of pediatric emergency medicine, professor of emergency medicine, and associate professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Georgia in Augusta. “That is the pinnacle of where we fail the community.”

Emergency department (ED) crowding is far from a new phenomenon; it has long been a way of life in both adult and children’s hospitals. But over recent years, the number of pediatric patients seeking care in EDs has been rising. The 2018 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data revealed that there were 130 million annual ED visits—25.6 million of those visits, or one-third, were made by children younger than 15 years of age. And the confluence of RSV, influenza, COVID-19 and pediatric behavioral health issues in late 2022 and early 2023 brought an unprecedented surge of ED visits from children.

“All four of those things were putting a lot of pressure on pediatric emergency departments and a lot of emergency departments in general,” says Nathan Timm, M.D., FAAP, medical director of emergency management at Cincinnati Children’s and professor in the department of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. “Crowding is a problem at most emergency departments in some form or another. That’s the tough part; there isn’t just one solution because the drivers of ED utilization are multifactorial.”

To examine the drivers of ED crowding—and to detail solutions—Timm, Lane and Toni Gross, M.D., MPH, FAAP, FAEMS, chief of the emergency department at Children’s Hospital New Orleans, put together an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement and companion technical report, both released in February 2023. They look at the crowding problem through the lens of three primary elements—input, throughput and output—and provide recommendations.

Input: How people enter the emergency department

This represents the number of patients who enter the ED by choice or by referral. For some patients, the ED has become a default location—or safety net—for a variety of non-emergency reasons, including lack of access due to geographical distance, a limited number of providers who accept Medicaid, and limited or inconvenient hours at primary care offices, which has been exacerbated by a trend of physicians working part time. In addition to these factors, a host of recent trends has accelerated input, putting significant resource strain on children’s hospitals.

“One thing that has contributed to crowding is the mental health surge occurring among pediatric and adolescent patients,” says Timm. From 2019 to 2020, behavioral health cases in the ED increased nearly 30% for children under 18 years old. In 2022, cases were still 20% higher than in 2019, according to data from Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). Many of these patients are driven to the ED because they have nowhere else to go, due to shortages of behavioral health outpatient facilities and providers. This is reflected in the volume that Timm sees at Cincinnati Children’s.

“We have a 120-bed mental health hospital that is separate from our medical center, and we still have wait times for children to go there,” Timm says. In some cases, there may be available mental health appointments at a clinic, Gross says, but they are during work and school hours, when it’s inconvenient for patients and families.

Read next: Children's Hospitals Address Surge of Respiratory Illnesses

Another trend contributing to input is the increasing complexity of medical insurance coverage, according to Gross. “Certain procedures, tests or referrals that require prior authorization can limit someone waiting to obtain those things in the outpatient setting, so they come to the emergency department because it’s faster and more convenient,” she says. “Or perhaps the health care plan doesn’t cover things easily, so the emergency department becomes easy for patients and families to use.”

Total ED input is one factor in crowding, but it’s the volatility of input that often causes difficulty in matching resources with demand. Since the pandemic, there has been less seasonality in emergency medicine, leading to more unpredictability.

According to Timm, it once was influenza in the winter, RSV in the spring, injuries in the summer. “COVID disrupted all that—because the viruses are now prevalent all year long,” he says. “Not necessarily to the extent that they were in the fall, but they’re still high relative to this time of year versus previous years.”

Input strategies

- Increase reliance on and advocacy for the medical home.

- Extend telehealth options, including for primary, acute, behavioral and long-term needs for chronically ill patients.

- Post ED wait times and enable ED appointments.

- Enhance access to primary care through additional hours and walk-in sick visits.

- Provide mobile-integrated health and community paramedicine programs for out-of-hospital evaluations.

- Integrate behavioral health care in primary care clinics and schools.

- Offer a mobile care clinic to reach patients who struggle with access to care.

- Advocate for CHGME and loan repayment to ensure adequate primary and specialty care workforce.

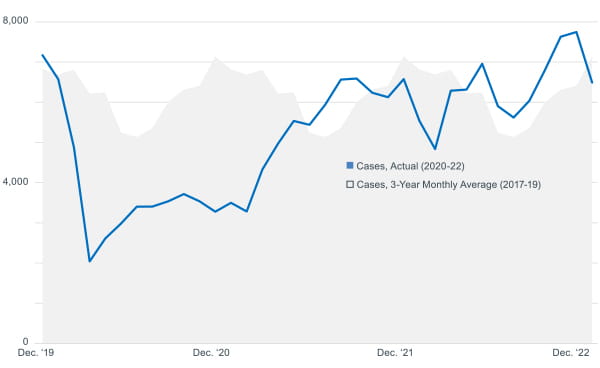

ED cases: Typical pattern versus recent pattern

of 2022, reaching record heights in December. Typical patterns of total ED volume also shifted in some cases after

2021, rising during typically low months and falling during typically high months. Data provided by Pediatric Health

Information System (PHIS).

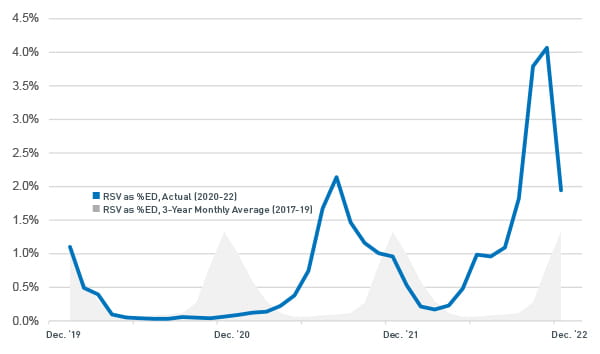

RSV cases: Typical pattern versus recent pattern

unpredictable with worse acuity overall. At the end of 2022 RSV increased more than three times its normal peak volume.

Throughput: How people move through the system

This is the way patients move through the system once they are in the ED. Delays can occur in this stage based on ED space and staffing limitations or misalignment; seasonal variations resulting in sudden surges of patients; or complex patient cases that require extensive evaluation and consultation from multiple disciplines and specialists. Other factors include language and cultural barriers, electronic medical documentation, and medical liability issues.

At Children’s Hospital of Georgia, space is a significant driver of ED crowding. Lane and her team see about 30,000 patient visits a year. To meet that demand statistically, Lane says the ED should have 20 beds; yet, it only has 16. Add to that the fact that more than a quarter of the beds in Lane’s ED are often occupied with mental or behavioral health patients, further limiting the capacity for other children coming in for emergency care.

Read next: Patient Transfer System Helps Children's Hospitals Handle Respiratory Surge

According to Timm, throughput depends heavily on operational processes such as staffing, room turnover and flow between the ED and departments like radiology, labs, respiratory care and pharmacy. Delaying any one of these things, he says, cascades down to the ED, causing backups that lead to crowding.

For example, a slowdown or shortage in environmental services can mean rooms on the floor are not turned fast enough for patients to transition out of the ED and into a bed. It could be that a radiology study takes a long time, or the lab is busy, so bloodwork is slow to come back, Gross says.

“It may not seem like all these things are related, but the entire operations of the hospital trickle down into the emergency department,” Gross says. “We need to look at all of the drivers that go into what’s happening and ask ourselves, ‘Where can we trim 5 minutes off here and 10 minutes off there?’”

Of all the challenges to throughput, staffing tops the list for pediatric EDs. Lane’s 10-person department doesn’t always have enough ED physicians to cover every day of the month, and there are limited options for on-call doctors. Then, there is the ever-present need to be prepared for a sudden surge or disaster.

“It’s one of the most difficult things that hospital planners and health care system planners have to balance,” says Gross. “You don’t want to be so efficient with your operations and resources that you don’t have capacity for a disaster or mass casualty incident or seasonal surge in patient activity.”

Throughput strategies

- Use fast-track assessment zones to match patient needs with resources more quickly.

- Put a provider in triage for faster assessments.

- Admit patients to pre-operative or post-operative care spaces.

- Leverage scribes for increased provider efficiency.

- Use a direct-admit referral process to admit patients without an ED stop.

- Utilize staff from different departments or roles creatively to fill non-clinical care needs.

- Offer bedside registration or kiosks to speed the process.

- Use capacity management systems to track patient flow resource availability throughout the system.

- Hold daily multi-departmental huddles to discuss throughput barriers and solutions.

- Treat patients in alternative spaces rather than taking up a bed when possible.

Output: How people leave the emergency department

Finally, output is how—and how quickly—patients transition out of the ED. A primary driver of crowding here is boarding—or holding an admitted patient in the ED—typically due to a lack of available staffed inpatient beds. Boarding has been exacerbated by the increasing number of patients coming to the ED for mental or behavioral crises, who may be boarded until they can move to a bed or another facility as needed.

Boarding is an all-too-familiar scenario for Timm, Lane and Gross. “It’s the biggest driver of our ED crowding problem,” Gross says. “That could potentially be because all of the beds are used up or because there’s not enough nursing staff to open all of the beds.”

Children’s Hospital New Orleans has a 46-bed emergency department; two are resuscitation beds and eight are reserved strictly for behavioral health patients. Yet, Gross says, for the last year and a half, not all 46 beds have been staffed due to the lingering nursing shortage brought on by the pandemic.

A more obscure disruption caused by the behavioral health crisis is the complexity of medical clearance, which is required to get patients out of the ED. Patients who present with a physical condition, like a broken arm, may be seen for a mental condition, like suicidal ideation, before they are medically cleared, which creates potential confusion in the system about when the patient is truly cleared for transfer or discharge. The time it takes to resolve the issue extends length of stay and reduces the availability of beds.

Beyond staff shortages and the behavioral health crisis, inpatient delays occur for a variety of reasons. According to the AAP technical report, these include complexity of care, lack of outpatient availability, prolonged length of stay, or lack of system coordination, to name a few.

Output strategies

- Ensure parallel processing to speed admission and lower length of stay.

- Adopt capacity alert systems to help enlist additional resources when needed.

- Create a dedicated observation unit that admits unscheduled patients from the ED.

- Open play areas or family waiting rooms for patients waiting for discharge to free up beds faster.

- Offer a “bridge clinic” for patients who need intensive services but can be safely discharged from the ed before meeting with a behavioral health provider.

- Develop an in-home care program for behavioral health patients after discharge, connecting them with clinician, therapeutic and peer caregiver support services.

- Seek funding from or partnerships with local and state agencies to develop solutions.]

- Utilize reverse triage to determine which inpatients can be discharged or transferred to a lower level of care.

The bottom line

ED crowding is such a complex problem that solutions require coordinated efforts across the health care delivery system. The key to all of it, according to Gross, is an organization-wide perspective of health care delivery.

“The biggest recommendation I have is to remember that this is a hospital issue, not an emergency department issue,” she says. “Any conversations, whether around brainstorming or making hard decisions, need to include multiple departments within the hospital.”

“ED crowding is not something that emergency departments can solve on their own,” adds Timm. “This really requires all hands on deck.”